Natural evolution strategy

Natural evolution strategies (NES) are a family of numerical optimization algorithms for black-box problems. Similar in spirit to evolution strategies, they iteratively update the (continuous) parameters of a search distribution by following the natural gradient towards higher expected fitness.

Contents |

Method

The general procedure is as follows: the parameterized search distribution is used to produce a batch of search points, and the fitness function is evaluated at each such point. The distribution’s parameters (which include strategy parameters) allow the algorithm to adaptively capture the (local) structure of the fitness function. For example, in the case of a Gaussian distribution, this comprises the mean and the covariance matrix. From the samples, NES estimates a search gradient on the parameters towards higher expected fitness. NES then performs a gradient ascent step along the natural gradient, a second order method which, unlike the plain gradient, renormalizes the update w.r.t. uncertainty. This step is crucial, since it prevents oscillations, premature convergence, and undesired effects stemming from a given parameterization. The entire process reiterates until a stopping criterion is met.

All members of the NES family operate based on the same principles. They differ in the type of probability distribution and the gradient approximation method used. Different search spaces require different search distributions; for example, in low dimensionality it can be highly beneficial to model the full covariance matrix. In high dimensions, on the other hand, a more scalable alternative is to limit the covariance to the diagonal only. In addition, highly multi-modal search spaces may benefit from more heavy-tailed distributions (such as Cauchy, as opposed to the Gaussian). A last distinction arises between distributions where we can analytically compute the natural gradient, and more general distributions where we need to estimate it from samples.

Search gradients

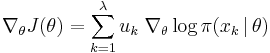

Let  denote the parameters of the search distribution

denote the parameters of the search distribution  and

and  the fitness function evaluated at

the fitness function evaluated at  . NES then pursues the objective of maximizing the expected fitness under the search distribution

. NES then pursues the objective of maximizing the expected fitness under the search distribution

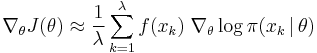

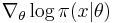

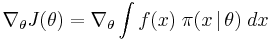

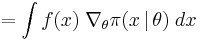

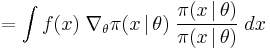

through gradient ascent. The gradient can be rewritten as

that is, the expected value of  times the log-derivatives at

times the log-derivatives at  . In practice, it is possible to use the Monte Carlo approximation based on a finite number of

. In practice, it is possible to use the Monte Carlo approximation based on a finite number of  samples

samples

-

.

.

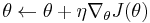

Finally, the parameters of the search distribution can be updated iteratively

Natural gradient ascent

Instead of using the plain stochastic gradient for updates, NES follows the natural gradient, which has been shown to possess numerous advantages over the plain (vanilla) gradient, e.g.:

- the gradient direction is independent of the parameterization of the search distribution

- the updates magnitudes are automatically adjusted based on uncertainty, in turn speeding convergence on plateaus and ridges.

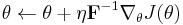

The NES update is therefore

-

,

,

where  is the Fisher information matrix. The Fisher matrix can sometimes be computed exactly, otherwise it is estimated from samples, reusing the log-derivatives

is the Fisher information matrix. The Fisher matrix can sometimes be computed exactly, otherwise it is estimated from samples, reusing the log-derivatives  .

.

Fitness shaping

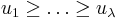

NES utilizes rank-based fitness shaping in order to render the algorithm more robust, and invariant under monotonically increasing transformations of the fitness function. For this purpose, the fitness of the population is transformed into a set of utility values  . Let

. Let  denote the ith best individual. Replacing fitness with utility, the gradient estimate becomes

denote the ith best individual. Replacing fitness with utility, the gradient estimate becomes

-

.

.

The choice of utility function is a free parameter of the algorithm.

Pseudocode

input:1 repeat 2 for

do //

is the population size 3 draw sample

4 evaluate fitness

5 calculate log-derivatives

6 end 7 assign the utilities

// based on rank 8 estimate the gradient

9 estimate

// or compute it exactly 10 update parameters

//

is the learning rate 11 until stopping criterion is met

See also

Bibliography

- D. Wierstra, T. Schaul, J. Peters and J. Schmidhuber (2008). Natural Evolution Strategies. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC).

- Y. Sun, D. Wierstra, T. Schaul and J. Schmidhuber (2009). Stochastic Search using the Natural Gradient. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- T. Glasmachers, T. Schaul, Y. Sun, D. Wierstra and J. Schmidhuber (2010). Exponential Natural Evolution Strategies. Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO).

- T. Schaul, T. Glasmachers and J. Schmidhuber (2011). High Dimensions and Heavy Tails for Natural Evolution Strategies. Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO).

![J(\theta) = \operatorname{E}_\theta[f(x)] = \int f(x) \; \pi(x \,|\, \theta) \; dx](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ed57139cb914a71c9fedc2109526661d.png)

![= \int \Big[ f(x) \; \nabla_{\theta} \log\pi(x \,|\, \theta) \Big] \; \pi(x \,|\, \theta) \; dx](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b287af1d5f5036719e505cc9f6b5a55d.png)

![= \operatorname{E}_\theta \left[ f(x) \; \nabla_{\theta} \log\pi(x \,|\, \theta)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2701ee4669988caf6fffa7413054c4b1.png)